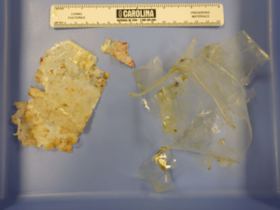

“Every single leatherback sea turtle that we’ve done a post-mortem exam on has had some sort of plastic in their GI tract. This probably wasn’t enough to kill her because it didn’t block the passage, but eating plastic is just not a good way to put on pounds, and it also can absorb toxins that could accumulate over time.”

Dr. Harms says the leatherback also had foam in her airways, indicating that she could have become entangled in a net or trawl.

Unfortunately, these types of events are happening more and more as trash is being introduced into the ocean. Marine debris enters the water in a variety of ways. It’s washed into rivers and streams and eventually flows into the sea. Debris can also come from ocean based industry and ships. Plastics washes around the ocean and eventually comes ashore or collects in one of five rotating garbage patches in the world’s oceans, called gyres. These are areas of floating debris that routinely choke out sea life.

Now, Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort is involved with a project using drones to document the amount of marine debris washing up on beaches around the world. Assistant Professor of the Practice of Marine Conservation Ecology Dave Johnston says the “Race For Water” project started about a year ago.

“We were approached, our research group and a group at Oregon State University, because we’d had experience doing surveys with this kind of stuff in other places; we have a lot of experience with marine debris up in the northwestern Hawaiian islands. So they approached us and we convinced them that one of the best ways to cover as much area while surveying the beaches is to use unmanned aerial systems.”

The project involves a group of sailors who are attempting to circumnavigate the globe in a trimaran, a racing sailboat similar to a catamaran, but with three hulls. The ship departed the port city of Bordeaux France on March 15th. It’s currently docked in Bermuda. During the 300 day voyage, the crew will document marine debris and visit gyres.

“Along their route, they’re visiting islands, we call those witness islands, that tend to collect the debris, plastics mostly, on their beaches. When the ship arrives at each one of these witness islands, they’ll go ashore, they’ll do some beach sampling, and they’ll use the unmanned aerial systems to actually sample those beaches.”

Instead the quad-copter drone you’re probably familiar with, the research group is utilizing a small Styrofoam airplane to collect data and images.

“You basically throw it in the air by hand, it’s got a pre-programmed flight path so it knows when to go, knows when to take the pictures. And then it essentially comes back and lands at your feet.”

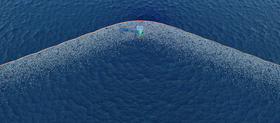

The drone is equipped with a specially designed red-edge camera that helps scientists detect the presence of plastics along beaches.

“When we look at the pictures that we’ve done in tests when you lay plastics out on a beach and fly the drone over with this camera the plastics just pop out very brightly so that’s going to help us speed up the analysis and just make it really clear how much of the beach is covered up with this macro plastic debris.”

The images collected during the drone flyovers are sent to Johnson and his students from the sailing vessel to the Duke Marine Lab in Beaufort for analysis. He says documenting debris in the oceans and on beaches allows researchers and managers to understand the origins and persistence of different types of plastic and how they interact with marine organisms.

“The biggest problem with plastic is that it’s around forever. We’ve developed something that’s very useful for us. It’s almost eternal. It breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces, but it accumulates in all parts of the ocean.”

Johnston says in 2010 alone between 4.8 and 7 million metric tons of trash entered the ocean. The impact of marine debris on animals is widespread, even on a tiny scale.

“It’s also in the plankton, it’s in jellyfish, it’s in all sorts of things. It’s everywhere.”

With this seemingly insurmountable problem, Johnston says drone technology is offering a first step in cleaning up our oceans. Even though fruition of this idea is probably decades away, locating the most impacted waters is key. With a better understanding of the origin and the amount of marine debris in our oceans, Johnston says we can move towards solutions. Using drones, the Race For Water project team will be able to get a detailed look at exactly what and how much trash is washing up on beaches around the world.

“It takes high resolution imagery so we can identify objects down to three quarters of an inch and then we get these images back so that allows us to be able to bring them into the lab and have students go through and estimate the amount of debris that might be on these beaches.”

During his past research trips, Johnston says it’s not uncommon to find old fishing gear, lighters, and toothbrushes along beaches. He’s also found unusual items like computer monitors, televisions, and portable toilet seats.

The first Race For Water surveys were conducted in the archipelago of the Azores. The information gathered by the drone was sent from Bermuda to the Beaufort lab where Johnston will be analyzing the images over the next few days.

“they get put together with the flight path of the drone, and they get stitched together into what we call a vague orthomosaic that’s essentially just a really big image of all of the images kind of to put it all together into one.”

This type of data collection may eventually be useful along the North Carolina coast. In addition to analyzing marine debris, drones could be used for a number of applications.

“Being able to do wildlife surveys, look at water quality. It’s coming and it’s really nice to see the positive contributions these types of devices and these kinds of scientific platforms can have.”

Drones could also prove useful along the coast following major storms and hurricanes in storm damage assessment. They could also be used to map the impact of climate change on reef habitats.

The Netherlands based initiative called “The Ocean Cleanup” is targeting garbage patches in oceans around the world to launch a system that would help eliminate plastic pollution. The concept uses ocean currents and long floating barriers similar to oil containment booms to gather debris without impacting wildlife. The Ocean Cleanup project will deploy a coastal pilot test next Spring, however the technology won’t be implemented at least for five more years.

Understanding how trash enters the ocean and where the currents take it is vital to cleanup efforts. In theory, the information collected through the Race For Water project could help other organizations, such as “The Ocean Cleanup” know where to place their trash collecting barriers to maximize efforts. Duke University Marine Lab’s Dave Johnston says all of the data from the Race For Water project will be available online.

“We have a system set up on the internet where people will be able to login to the website and actually see the data, see the reflectance maps and see the actual flights of the drones. See for themselves what we’ve found and be able to download the data if they want to use it for other things.”

When the Race For Water sailing crew leaves Bermuda, they’re headed for New York where Johnston says they’ve been invited to give a briefing to the United Nations Environmental Programme about the project.

To track the progress of the Race For Water Odyssey, go to www.raceforwater.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.