Plastic litter is one of the most significant problems facing the world's marine environments. Yet in the absence of a coordinated global strategy, an estimated 20 million tons of plastic litter enter the ocean each year.

A new report by authors from UCLA School

of Law's Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment and UCLA's

Institute of the Environment and Sustainability explores the sources

and impacts of plastic marine litter and offers domestic and

international policy recommendations to tackle these growing problems — a

targeted, multifaceted approach aimed at protecting ocean wildlife,

coastal waters, coastal economies and human health.

"Stemming the Tide of Plastic Marine Litter: A Global Action Agenda," the

Emmett Center's most recent Pritzker Environmental Law and Policy

Brief, documents the devastating effects of plastic marine litter,

detailing how plastic forms a large portion of our waste stream and

typically does not biodegrade in marine environments. Plastic marine

litter has a wide range of adverse environmental and economic impacts,

from wildlife deaths and degraded coral reefs to billions of dollars in

cleanup costs, damage to sea vessels, and lost tourism and fisheries

revenues. The brief describes the inadequacy of existing international

legal mechanisms to resolve this litter crisis, calling on the global

community to develop a new international treaty while also urging

immediate action to implement regional and local solutions.

"Plastic marine litter is a growing global

environmental threat imposing major economic costs on industry and

government," said report co-author Mark Gold, an associate director of

the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

Marine plastic pollution slowly degrades and has spread to every corner

of the world's oceans, from remote islands to the ocean floor.

Voluntary half-measures are not preventing devastating global impacts to

marine life, the economy and public health. Although there is no one

panacea, we have identified the top 10 plastic pollution–prevention

actions that can be implemented now to begin drastically reducing

plastic marine litter."

In "Stemming the Tide of Plastic Marine Litter," the

authors review the universe of studies, policies and international

agreements relevant to the problem and provide a suite of

recommendations to achieve meaningful reductions in plastic marine

litter. The report's "Top 10" list of recommended actions includes a new

international treaty with strong monitoring and enforcement mechanisms;

domestic and local regulatory actions, such as bans of the most common

and damaging types of plastic litter; extended producer-responsibility

programs; and the creation of an "ocean friendly" certification program

for plastic products.

"Because global

mismanagement of plastic is fueling the growing marine litter problem,

policy responses are needed at all levels, from the international

community of nations down to national and local communities," said

report co-author Cara Horowitz, executive director of the Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment.

"We can act now to rapidly scale up effective policies and programs to

address plastic marine litter. And hopefully, international

collaboration to reduce plastic litter will lay a foundation for broader

cooperation on other significant issues affecting the health of our

oceans."

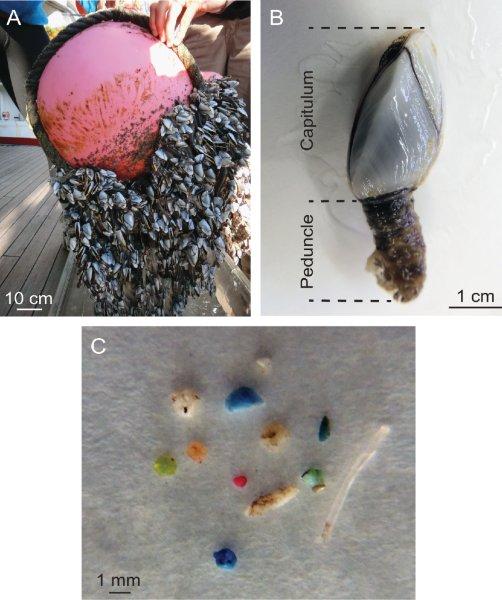

Plastic marine litter has its origins in both land- and ocean-based sources, from untreated sewage and industrial and manufacturing sites to ships and oil and gas platforms. Pushed by the natural motion of wind and ocean currents — often over long distances — the litter is present in oceans worldwide, as well as in sea floor sediment and coastal sands. As the particles break down and disperse, they have a wide range of adverse environmental, public health and economic consequences with the potential to kill wildlife, destroy natural resources and disrupt the food chain.

The Pritzker Environmental Law and Policy Briefs

are published by UCLA School of Law and the Emmett Center on Climate

Change and the Environment in conjunction with researchers from a wide

range of academic disciplines and the broader environmental law

community. They are made possible through a generous donation by Anthony

"Tony" Pritzker, managing partner and co-founder of The Pritzker Group.

The briefs provide expert analysis to further public dialogue on issues

impacting the environment. All papers in the series are available here.

UCLA School of Law, founded

in 1949, is the youngest major law school in the nation and has

established a tradition of innovation in its approach to teaching,

research and scholarship. With approximately 100 faculty and 1,100

students, the school pioneered clinical teaching, is a leader in

interdisciplinary research and training, and is at the forefront of

efforts to link research to its effects on society and the legal

profession.

Great Pacific Garbage Patch ...