On my 2009 expedition to the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, otherwise known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” I collected a bunch of barnacles, along with samples of a lot of other organisms that were growing on the debris, because I was interested in seeing what species were there. Gooseneck barnacles look kind of freaky. Like acorn barnacles (the ones that more commonly grow on docks), they’re essentially a little shrimp living upside down in a shell and eating with their feet. Unlike acorn barnacles, gooseneck barnacles have a long, muscular stalk.

This

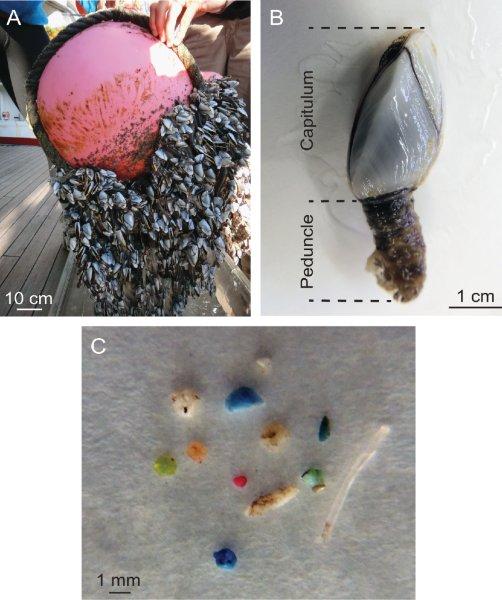

is a figure from our paper that shows (a) barnacles growing on a buoy;

(b) a closeup of an individual barnacle. The body is inside the white

shell, and the stalk is just muscle; and (c) Plastic that we pulled out

of a single barnacle’s guts.

Thinking about it logically, it makes a lot of sense that gooseneck barnacles are eating plastic. They are really hardy, able to live on nearly any floating surface from buoys to turtles, so they’re very common in the high-plastic areas of the gyre. They live right at the surface, where tiny pieces of buoyant plastic float. And they’re extremely non-picky eaters that will shove anything they can grab into their mouth.

But, since I didn’t really collect barnacles with this study in mind, I didn’t have enough samples to figure out how widespread this phenomena might be. Fortunately, I’d been lucky enough to collaborate with the wonderful Sea Education Association and one of their chief scientists, Deb Goodwin, for several years. SEA kindly took samples for us, and Deb, once a perfectly respectable remote sensing expert, got deep into some pretty smelly barnacle guts.

After dissecting 385 barnacles, Deb and I found that 33.5% – one-third – had plastic in their guts. Most barnacles had eaten just a few particles, but we found a few that were absolutely filled with plastic, to a maximum of 30 particles, which is a lot of plastic in an animal that is just a couple inches long. We also analyzed the type of plastic in the barnacle guts, and found that it was approximately representative of plastic on the ocean surface – the barnacles are probably just grabbing whatever they come across and shoving it into their mouths. Barnacles are perfectly capable of pooping out plastic – I observed plastic packaged up in fecal pellets, ready to be excreted the next time the barnacle had access to a couple minutes and a magazine – so it is very likely that more barnacles are eating plastic than we were able to measure.

The

circles show where we sampled, and the dark part of the circle is the

percentage of barnacles that had eaten plastic. The inset shows where we

were in the ocean – the rectangle between North American and Hawaii.

Gooseneck barnacles aren’t necessarily incredibly central to the North Pacific Gyre ecosystem. The barnacles are voracious predators, but since plastic is so patchy, it’s not clear that they eat enough zooplankton to really affect the ecosystem – and a lot of the food I found in the barnacle guts were their own cyprid babies.

(Barnacles are nasty cannibals, apparently.) They’re eaten by a few predators – a pretty little sea slug and some crabs – but fish don’t seem that interested in barnacles, maybe because those fish didn’t evolve with a ton of floating debris. If barnacles are an important prey item, it is possible that their ingestion of plastic particles could transfer plastic or pollutants through the food web, but it is far from clear this is the case.

However, the most dire effects could be the most subtle. The subtropical gyres are 40% of the entire earth’s surface, and so they are very important to controlling the way that nutrients and carbon move around in the ocean. The microbes and animals that live on plastic debris are not the same as the microbes and animals that float around in the ocean, and may not act in the same way. It’s such a cliché for a scientist to call for more research, but we just don’t understand enough about the way that the ocean works, and enough about the way that plastic affects the ocean, to really say what the effects of barnacles eating plastic might be.

And the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre is a really

nice place! It’s good to know what is going on there!

I’ll be back in a couple weeks to do another behind-the-scenes post on a second debris-related paper! In the meantime, I’m happy to answer your questions about the barnacles.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.