Published by Save the Bay

Myth: Recycling plastic bags is the best solution to addressing the litter problem.

Fact: Plastic bag recycling is costly and just doesn’t work.

Despite a 15-year statewide effort in California, recycling plastic bags has failed. The California Integrated Waste Management Board estimates that less than 5 percent of all single use plastic bags in the state are actually recycled.

Plastic bags cost municipal recycling programs millions each year, when bags jam sorting equipment at recycling facilities. In San Jose, less than four percent of plastic bags are recycled and work stoppages from jammed bags cost the City approximately $1 million per year.

Failed recycling efforts means billions of plastic bags are thrown away, blow onto our streets and float into our waterways. Plastic bags are the quintessential litter item: there are billions of them, they are used for a few short minutes, and they are light and easily transportable.

Myth: Recycled plastic bags are a valuable commodity.

Fact: The market for recycled plastic bags is small and unstable.

At the moment, a single manufacturer, purchases 70 percent of the plastic bags recovered nationwide, to make outdoor decking. In 2008, Newsweek reported that the company lost $75 million in the previous year, raising questions about the long-term viability of the end market. Some curbside programs will take plastic bags if they are bundled, but the commodity is low grade and brings a low price, partly because it gets dirty during handling and transportation. Even the plastic bag industry doesn't use its own post-consumer material. Recyclers are sometimes forced to stockpile bales of bags or even pay to get rid of them.

Myth: Bans or fees on plastic bags will just push people to use more paper bags.

Fact: With well-designed policies that address both plastic and paper bags, consumers will switch to reusable cloth bags.

The legislation supported by Save The Bay and other advocates covers all single-use bags, both paper and plastic. This is a proven way to decrease the use of both kinds of bags in favor of reusable bags - which are inexpensive and long-lasting - ultimately saving retailers and consumers money. Every year in the U.S, consumers and retailers spend billions of dollars on excessive quantities of single-use bags that have an average use time of 12 minutes.

Myth: A fee on plastic bags didn't work in Ireland.

Fact: Ireland's bag fee dramatically reduced plastic bag usage and plastic bag litter.

Ireland's Environmental Protection Agency submitted a letter to the San Jose City Council rebutting the American Chemistry Council’s (ACC) false claims about Ireland's bag fee. In this letter, Ronan Mulhall of the Waste Policy division confirms that plastic bag litter dropped by 93 percent and plastic bag use decreased by approximately 90 percent in the year following the Plastic Bag Levy. Ireland later increased their fee to approximately 33 cents (US). The Irish EPA reports that these dramatically lower levels of plastic bag use and litter are being maintained.

Myth: Fees on single use bags will negatively impact low income people.

Fact: No one has to pay the fee.

A single-use bag fee is only charged if you do not bring your own bag. Lower income communities (some of the most blighted by plastic bag litter) are already paying for plastic bags through city taxes and increased food and retail prices. Every bag fee policy currently under consideration at the local and state level would either subsidize reusable bags for low-income residents or exempt low-income residents from paying the fees.

Myth: Single-use bag bans or fees are bad policy in this time of economic crisis.

Fact: Reducing the use of single-use plastic and paper bags will save us all money.

Retailers currently embed 2 to 5 cents per plastic bag and 5 to 23 cents per paper bag in the price of goods—adding $30 or more per person annually in hidden costs. In contrast, when consumers use reusable bags, retailers save money and can lower prices. Many grocers offer a 5-cent rebate for bringing your own bag, which can add up to about $60 in savings per year for an average family.

Bags clog storm drains and recycling equipment, costing cities millions, and bag litter lowers property values and degrades recreational areas. In addition to the out-of-pocket cost passed on from the retailer to consumers, California taxpayers spend approximately $25 million every year to collect and landfill plastic bags.6 San Jose City staff estimates that it costs at least $3 million annually to clean plastic bags from creeks and clogged storm drains.

Single-use bag production depletes resources and contributes to carbon emissions and global warming. We consume approximately 14 million trees8 and 12 million barrels of oil9 to produce the billions of plastic and paper bags we throw away in the United States every year.

Myth: Plastic bag litter isn't really a problem for the environment.

Fact: 1.37 million plastic bags were removed from coastal areas worldwide in one day last year.

Plastic trash entangles, suffocates, and poisons at least 267 animal species worldwide. According to the California Coastal Commission, up to 80 percent of all marine debris is plastic, which never biodegrades.

Plastic bags were the second largest item of litter picked up by volunteers during the Ocean Conservancy's 2008 International Coastal Cleanup Day. It is estimated that one million plastic bags pollute the Bay every year. Scientists recently measured 334,271 pieces of plastic per square mile in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Myth: Education about responsible use and disposal of plastic bags will reduce litter.

Fact: Unfortunately, public education hasn't worked, despite massive public investment.

Huge amounts of money have been spent on public education about litter. One example is CalTrans' "Don't Trash California" campaign. Yet, we still see our highways coated in bags, cups, and cigarette butts. A fee on single use bags provides an incentive to consumers to change their behavior and switch to reusable bags.

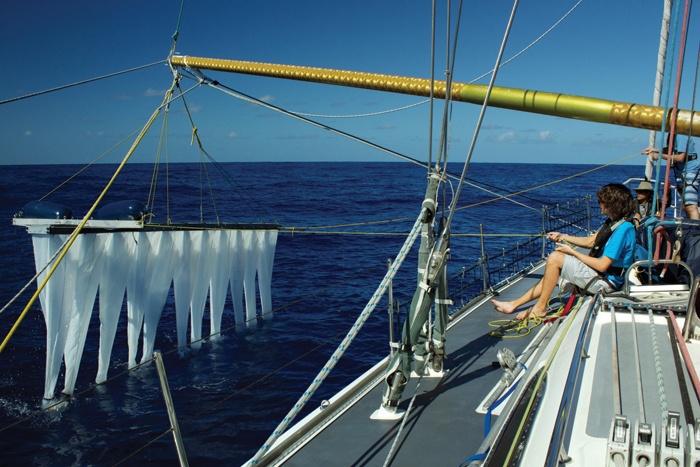

Though The Ocean Cleanup estimates it can collect the

majority of plastic mass from the world’s oceanic gyres, it does not

think it can collect any microplastics, particles less than five

millimetres (mm) (or even one mm, according to some researchers). In

fact, under the modelled conditions, no plastics smaller than two

centimetres were captured.

“There appears to be a sink for microplastics that is

already in place”, Slat tells me. “We don’t know what it is, but it

could be that fish are eating it and therefore they cannot be found

anymore near the surface of the water – there should be a lot more of

them, but there aren’t. It could also be that they sink, that they are

deeper in the water column – we have some evidence for that.”

Slat emphasises that, by capturing 95 per cent of the mass

of oceanic plastic, The Ocean Cleanup would prevent many microplastics

from being created, as larger plastic items photodegrade into

ever-smaller pieces in pelagic conditions. However, microplastics don’t

just come from larger bits of plastic – some start off micro, which is

of increasing concern to scientists and environmental campaigners.

‘Primary microplastics’ are popular in beauty products as

abrasives and exfoliants, especially in face washes, toothpaste, shaving

cream and shower gel – and these microbeads are now commonly made from

plastic rather than natural materials (be sure to read your ingredient

list!). Microplastics can also originate in household washing machines,

due to the shedding of synthetic textile fibres – in either case, these

tiny bits of plastic are too small to be extracted by sewage treatment

works, and slip through to marine ecosystems with devastating

consequences.

While there’s little that can currently be done about

microplastics that break away from larger masses, there’s now an

international campaign, ‘Beat the Microbead’, which was launched by the

Plastic Soup Foundation in 2012. As a result, a number of multinational

cosmetic companies have pledged to phase out microbeads, though many

have not set definite timetables.

Moreover, the Dutch government is

pushing for a ban in Europe, which would be similar to bans in some US

states; following concern about microplastic dispersion in the Great

Lakes, Illinois and New York have banned the manufacture and sale of

products containing microbeads, with Michigan and Ohio looking to follow

suit.

To find out more information, visit: www.beatthemicrobead.org

(image courtesy of

(image courtesy of