Who's flushing plastic pollution into the oceans, creating tiny time bombs that kill fish, birds and sea turtles ingesting what they think is food? That question has been around since 1997, when the "Great Pacific Garbage Patch" was discovered, and a new mathematical model could provide the tool needed to track down the culprits.

The model shows that

pollution can cross what scientists thought were boundaries between

oceans and especially its five gyres — large circular currents that are

now known to trap floating debris in what have been dubbed garbage

patches. Most of that trash is not even visible: It's tiny plastic

pellets floating at or just below the surface.

"The breaking of the

geographic ocean boundaries should shift the way people think of where

oceans begin and end," modeler and mathematician Gary Froyland told NBC

News. "The interactions that we've shown between the different oceans

shows that no ocean is isolated and that local effects can have impacts

far from the source."

Froyland and two

colleagues at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia,

described their model in a paper published Tuesday in the peer-reviewed journal Chaos.

The work builds off an earlier, but less sophisticated, online tool (adrift.org.au) that allows users to project how plastic pollution travels in ocean currents.

The trio's math comes

from a field known as ergodic theory, which has been used to study

interconnectedness — think complex systems like the Internet, or even

humanity.

For their model, the

team divided the entire ocean into seven regions whose waters mix very

little. Their projections tracked well with existing ocean circulation

models and refined those to the point where they found that parts of the

Pacific and Indian oceans are actually most closely coupled to the

south Atlantic, while part of the Indian Ocean really belongs in the

South Pacific.

A follow-up study will

look at how porous those boundaries are. "We first wanted to see where

the boundaries are, the next step is to study the amount of plastic

crossing these boundaries," said Erik van Sebille, an oceanographer with

the team.

Scientists not involved in the modeling welcomed the tool.

"I could imagine using

their model to generate hypotheses about the likely source regions of

debris in each of the 'garbage patches' that could be tested with

on-the-ground sampling in these coastal regions," said Kara Lavender

Law, an oceanographer with the Sea Education Association in Woods Hole,

Mass.

"We already know that

once debris leaves a harbor or coastline it is fairly quickly carried to

the open ocean to these subtropical accumulation zones," she adds, "but

what we might not have guessed is that debris in the accumulation zones

may have originated from the next ocean basin over."

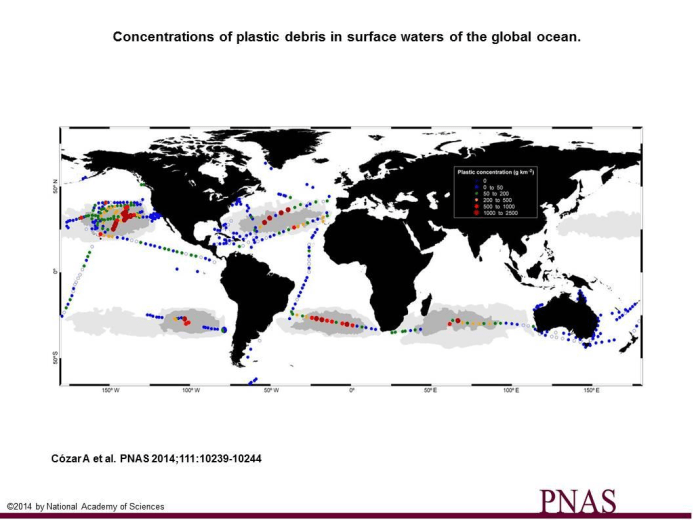

For Spanish marine ecologist Andres Cozar Cabanas, who published a study last July that mapped plastic ocean debris across the globe, the model shows that plastic pollution "is a global issue that can be effectively addressed only … at a global level."

That's exactly how the

Aussie trio want the tool to be used. "At a political level," says

Froyland, "the realization that even the garbage patches exchange

garbage may make governments realize that 'we're all in it together,'

hopefully producing some global action."

NOAA Marine Debris Program

More about Ocean Gyres:

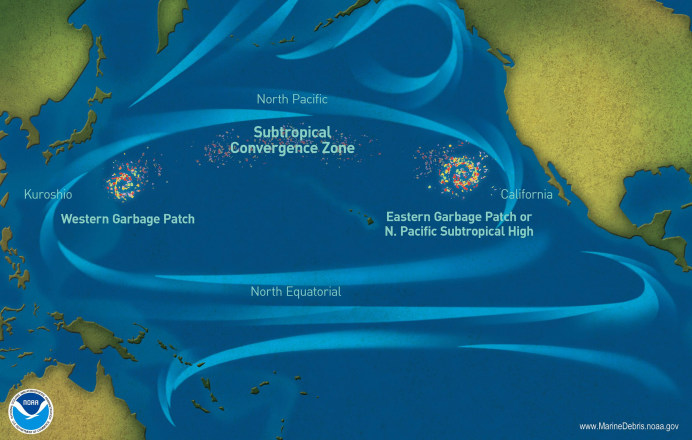

The great Pacific Garbage is a collection of marine debris located in

the North Pacific Ocean. The high-pressure area between the U.S. states

of Hawaii and California is the precipitating factor for the Pacific

Garbage phenomenon. The area lies in then centre of the North Pacific

Subtropical Gyre, which is a circular ocean currents which has been

formed by Earth wind patterns and the forces created by the rotation of

Earth. The middle of the gyre is very calm. The circular motion of the

Gyre pulls in the debris into the center. A similar garbage patch exists

in the Atlantic Ocean, in the North Atlantic Gyre.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.