There's less than expected on the surface. Scientists are trying to find where in the ocean it's gone.

Published in National Geographic July 15, 2014

by Laura Parker

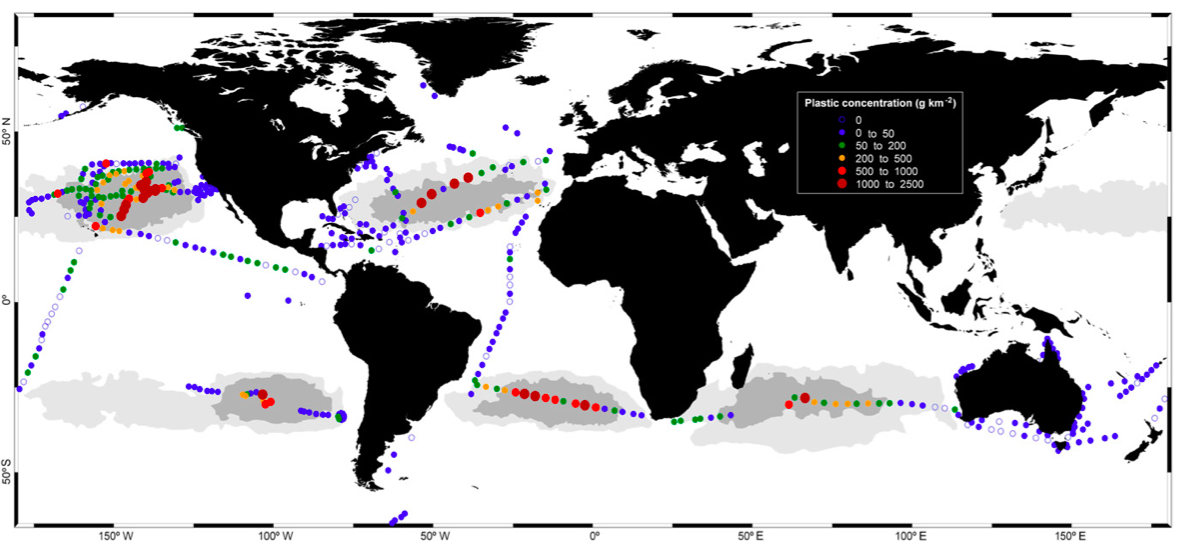

When marine ecologist Andres Cozar Cabañas and a team of researchers completed the first ever map of ocean trash, something didn't quite add up.

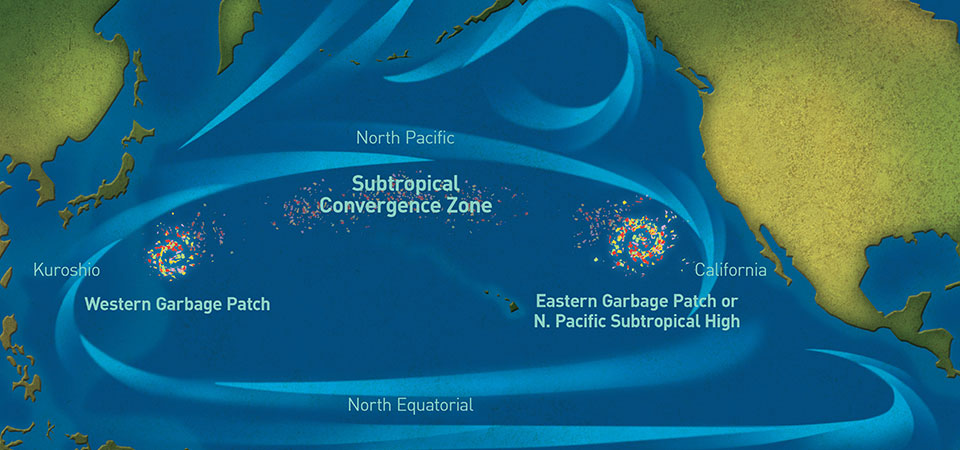

Their work, published this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, did find millions of pieces of plastic debris floating in five large subtropical gyres

in the world's oceans.

But plastic production has quadrupled since the 1980s, and wind, waves, and sun break all that plastic into tiny bits the size of rice grains. So there should have been a lot more plastic floating on the surface than the scientists found.

"Our observations show that large loads of plastic fragments, with sizes from microns to some millimeters, are unaccounted for in the surface loads," says Cozar, who teaches at the University of Cadiz in Spain, by e-mail. "But we don't know what this plastic is doing.

The plastic is somewhere—in the ocean life, in the depths, or broken down into fine particles undetectable by nets."

What effect those plastic fragments will have on the deep ocean—the largest and least explored ecosystem on Earth—is anyone's guess. "Sadly," Cozar says, "the accumulation of plastic in the deep ocean would be modifying this enigmatic ecosystem before we can really know it."

Follow Laura Parker on Twitter

But plastic production has quadrupled since the 1980s, and wind, waves, and sun break all that plastic into tiny bits the size of rice grains. So there should have been a lot more plastic floating on the surface than the scientists found.

"Our observations show that large loads of plastic fragments, with sizes from microns to some millimeters, are unaccounted for in the surface loads," says Cozar, who teaches at the University of Cadiz in Spain, by e-mail. "But we don't know what this plastic is doing.

The plastic is somewhere—in the ocean life, in the depths, or broken down into fine particles undetectable by nets."

What effect those plastic fragments will have on the deep ocean—the largest and least explored ecosystem on Earth—is anyone's guess. "Sadly," Cozar says, "the accumulation of plastic in the deep ocean would be modifying this enigmatic ecosystem before we can really know it."

But where exactly is the unaccounted-for plastic? In what amounts? And how did it get there?

"We must learn more about the pathway and ultimate fate of the 'missing' plastic," Cozar says.

Plastic, Plastic Everywhere

One reason so many questions remain unanswered is that the

science of marine debris is so young. Plastic was invented in the

mid-1800s and has been mass produced since the end of World War II. In

contrast, ocean garbage has been studied for slightly more than a

decade.

"This is new mainly because people always thought that the

solution to pollution was dilution, meaning that we could turn our head,

and once it is washed away—out of sight, out of mind," says Douglas Woodring, co-founder of the Ocean Recovery Alliance, a Hong Kong-based charitable group working to reduce the flow of plastic into the oceans.

The North Pacific Garbage Patch, a loose collection of

drifting debris that accumulates in the northern Pacific, first drew

notice when it was discovered in 1997 by adventurer Charles Moore as he sailed back to California after competing in a yachting competition.

A turning point came in 2004, when Richard Thompson, a British marine biologist at Plymouth University, concluded that most marine debris was plastic.

Research on marine debris is also complicated by the need

to include a multidiscipline group of experts, ranging from

oceanographers to solid-waste-management engineers.

"We are at the very early stages of understanding the accounting," says Kara Lavender Law, an

oceanographer at the Sea Education Association, based in Cape Cod,

Massachusetts. "If we think ten or a hundred times more plastic is

entering the ocean than we can account for, then where is it? We still

haven't answered that question.

"And if we don't know where it is or how it is impacting

organisms," she adds, "we can't tell the person on the street how big

the problem is."

Law, along with Thompson, is one of 22 scientists researching marine debris for the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis

at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The group is grappling

with some of these questions and plans to publish a series of papers

later this year.

One of the most significant contributions made by Cozar's

team, says Law, was data collected in the Southern Hemisphere: "I can't

tell you how rare that is."

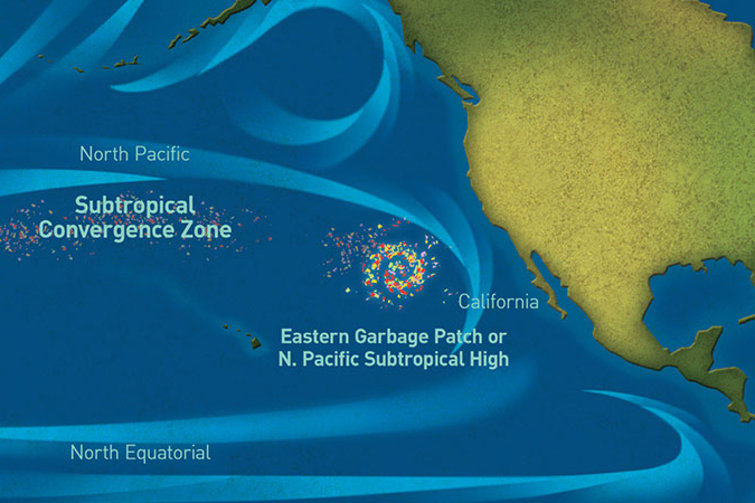

New Maps Document Floating Plastic Trash

Tens of thousands of tons of plastic garbage float

on the surface waters in the world's oceans, according to researchers

who mapped giant accumulation zones of trash in all five subtropical

ocean gyres. Ocean currents act as "conveyor belts," researchers say,

carrying debris into massive convergence zones that are estimated to

contain millions of plastic items per square kilometer in their inner

cores.

NG STAFF, JAMIE HAWK. SOURCE: ANDRÉS COZAR, UNIVERSITY OF CÁDIZ, SPAIN

One Answer

Cozar's team was part of the Malaspina expedition

of 2010, a nine-month research project led by the Spanish National

Research Council to study the effects of global warming on the oceans

and the biodiversity of the deep ocean ecosystem.

Originally Cozar was

assigned to study small fauna living on the ocean surface. But when tiny

plastic fragments kept turning up in water samples collected by the

expedition scientists, Cozar was reassigned to assess the level of

plastic pollution.

The two-ship expedition spent nine months circumnavigating

the world. But Cozar also used data gathered by four other ships that

had traveled to the polar regions, the South Pacific, and the North

Atlantic to complete the map.

The team analyzed 3,070 water samples. "One of the most

striking observations was the conspicuous presence of plastic in the

surface samples, even thousands of kilometers from the continents," he

says. "The plastic garbage patch in the South Atlantic Gyre was one of

the most striking."

See how scientists and artists have gathered and studied ocean debris to put the problem of trash into perspective.

Cozar says that one answer to the missing-plastic mystery

is that some of the tiniest bits of plastic are being consumed by small

fish, which live in the murky mesopelagic zone, 600

feet to 3,300 feet (180 to 1,000 meters) below the surface.

Little is

known about these mesopelagic fish, Cozar says, other than that they're

abundant. They hide in the darkness of the ocean to avoid predators and

swim to the surface at night to feed.

"We found plastics in the stomachs of the fishes collected

during Malaspina's circumnavigation," he says. "We are working on this

now."

One of the most common mesopelagic fish is the lantern fish, which

lives in the central ocean gyres and is the main link in the tropical

zone between plankton and marine vertebrates. Because lantern fish serve

as a primary food source for commercially harvested fish, including

tuna and swordfish, any plastic they eat ends up in the food chain.

"There are signs enough to suggest that plankton-eaters,

the small fishes, are important conduits for plastic pollution and

associated contaminants," Cozar says. "If this assumption is confirmed,

the impacts of a man-sustained plastic pollution could extend over the

ocean predators on a large scale."

U.S. State Department hosted two-day conference earlier this week which

saw new executive actions announced to protect the oceans and cut

marine pollution.

U.S. State Department hosted two-day conference earlier this week which

saw new executive actions announced to protect the oceans and cut

marine pollution.