published by Steven Jone in The Hill — 01/03/19

Dozens of U.S. cities made 2018 the year of the plastic straw ban. But if we really want to reduce the plastic pollution rapidly amassing in our oceans, 2019 must be the year we challenge the fossil fuel industry’s plan to aggressively expand plastic production.

Yes, those straw bans help. Straws contribute to ocean plastic pollution that’s expected to outweigh all the fish in the sea by 2050. Those who pushed the anti-straw #StopSucking campaign — and journalists who gave high-profile coverage to the plastic-pollution crisis — deserve tremendous credit for the quick adoption of plastic straw bans over the past year. Along with earlier plastic-bag bans and restrictions on Styrofoam packaging, these actions can significantly reduce the flow of plastic into our oceans.

But it’s not enough. These gains could easily be wiped out by dozens of new plastic-production plants being built along the Gulf Coast and in the Rust Belt. They’re part of the fossil fuel industry’s stated goal of increasing plastic production by 40 percent over the next decade.

Even though we’re already dumping about 8 million tons of plastic into our oceans each year — which chokes marine life, absorbs toxins, travels throughout the ocean food web and doesn’t break down for decades — Big Oil wants to make more plastic. These ethane “cracker” plants would use our oversupply of cheap, fracked natural gas to create plastic pellets, the basic building blocks of cheap plastic packaging and products.

Most of that plastic will end up in our oceans, landscapes and landfills. Almost 80 percent of the plastic we produce ends up in our landfills and the natural environment, a figure that could rise now that China has stopped accepting our plastic recycling.

Yet, ExxonMobil, Shell, Dow, Formosa Plastics and other companies are planning to spend $180 billion on increased plastic production in the coming years.

For example, ExxonMobil is now trying to build the world’s largest plastics plant in Texas, in partnership with Saudi Arabia thanks to a deal cut by President Trump, using about $1 billion in subsidies from Texas taxpayers. That means this project is paying a murderous regime and highly profitable oil company to create pollution we’ll all pay for later.

Another massive plastic plant is slated for the banks of the Mississippi River, transforming an agricultural and wetland habitat into a dirty petrochemical plant. People nearby in the community of St. James Parish, Louisiana — in a predominantly African American district already known as Cancer Alley because of the toxins spewed by local petrochemical plants — are fighting the plastics plant proposed by the Taiwanese company Formosa Plastics.

This is a company that has been heavily fined for spilling plastic pellets into Texas waterways, polluting the air in Louisiana, and a 2004 explosion and fire at its plant in Illinois. The fire killed five workers and forced the evacuation of a nearby town.

So even if it doesn’t explode or sicken its impoverished neighbors, even if its industrial runoff doesn’t contaminate the region’s vital seafood industry, even in the best-case scenario where nothing goes terribly wrong, we still end up with a bunch of cheap plastic we don’t want or need.

This plastic buildout is being repeated in Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Mississippi and the other states now processing applications for plastic plants and the pipelines that feed them with fracked natural gas. Each project spews pollution into our air and water as it produces endless amounts of plastic.

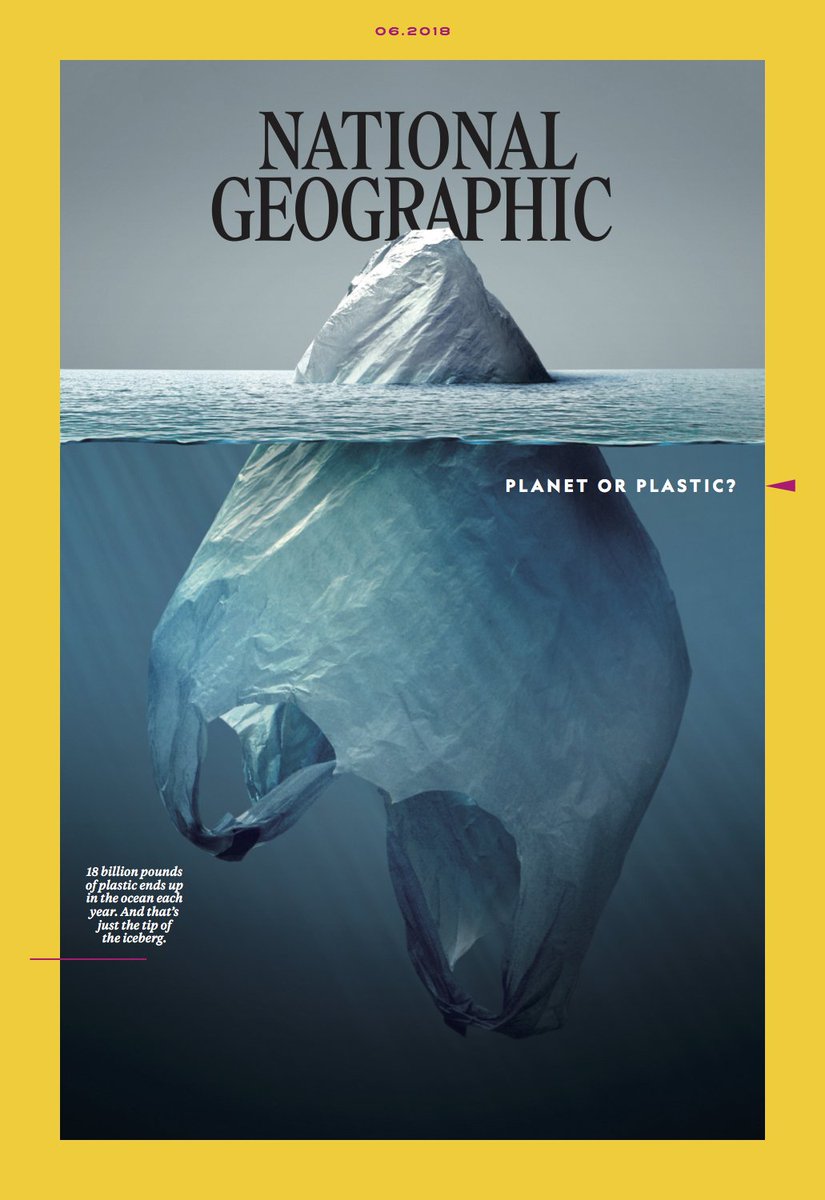

Now, 2019 will be a critical year in deciding whether we slow down this plastic-pollution juggernaut or simply let the problem get worse and pass it on to the next generations. As National Geographic put it in a special issue this year, it’s time to choose between “plastic or planet.” Let’s choose the planet.

Steven T. Jones is a media specialist with the Center for Biological Diversity. Jones was previously editor-in-chief of the San Francisco Bay Guardian. He worked as a journalist for 24 years, including covering coastal and environmental issues for seven different newspapers.

A blog set out to explore, archive & relate plastic pollution happening world-wide, while learning about on-going efforts and solutions to help break free of our addiction to single-use plastics & sharing this awareness with a community of clean water lovers everywhere!

Monday, January 7, 2019

The war on plastic is heating up

published on the Mother Nature Network, January 2, 2019 by Noel Kirkpatrick

Across the globe, we're getting serious about reducing the use of plastic bags, utensils and containers.

Plastic bags may be convenient for us, but they're not terribly convenient for the environment. (Photo: Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images)

Plastic bags are just about everywhere, but their days seem to be increasingly numbered.

As awareness of the dangers of plastic bags continues to rise — from the threat to wildlife to the fact that they aren't biodegradable — more groups are taking actions to limit their presence.

The media is also taking notice. National Geographic's magazine cover shocked many readers.

The company also launched a campaign called #PlanetorPlastic to raise awareness of plastic pollution and will stop wrapping its magazines in plastic.

Of course, the war on plastic bags isn't new by any stretch. In 2002, Bangladesh became the first country to ban the use of thin plastic bags after it was discovered that a build up of the bags choked the country's drainage systems during flooding. In the almost 20 years since then, more countries and individual cities have taken action, including taxing the use of the bags or following Bangladesh's lead and outright banning them.

And the scope of the war is expanding beyond bags. Plastic straws, bottles, utensils and food containers are all fronts in this ongoing battle, as the convenience and low monetary cost of single-use plastic items is outweighed by a desire for a sustainable lifestyle.

South Korea and Taiwan leading the way in Asia

Beginning in 2019, grocery stores and supermarkets in South Korea can no longer provide single-use plastic bags to shopper except to hold "wet" food like fish and meat. Instead, they will be required by law to provide cloth or paper bags that can be either recycled or reused. The penalty for violating this law is a fine up to 3 million won (about $2,700 U.S.).

The Taiwanese government announced plans to steadily phase out the use of plastic straws, bags, utensils, cups and containers by 2030.

By 2019, fast-food chains will no longer be allowed to supply plastic straws for in-store use, meaning no plastic straws for someone having a meal inside the restaurant. By 2020, free plastic straws will be banned from all eating and drinking establishments. By 2025, the public will have to pay for to-go straws, and by 2030, there'll be a blanket ban on the use of plastic straws entirely.

Other plastic goods, including plastic bags, utensils and food containers will face a similar phase-out process. If a retail company files invoices for uniforms, which many do, according to the Hong Kong Free Press, then that company will no longer be allowed to offer free versions of those products after 2020. While that might seem like a loophole of sorts — "Our employees will no longer have to buy or wear uniforms we provide so we can continue to offer plastic items." — it's one that will close by 2030 when another blanket ban on those products will be introduced.

The minister who oversees this program, Lai Ying-ying, emphasized that this is more than just a job for the Taiwanese Environmental Protection Agency; the entire country, he said, needs to rally behind it if it's to be successful. It's a daunting challenge as the Taiwanese EPA estimates that a single Taiwanese person uses around an average of 700 plastic bags a year.

Lofty goals in the European Union

A man shops in a Greek public market. The Greek government banned free plastic bags at the start of 2018. (Photo: Giannis Papanikos/Shutterstock)

A man shops in a Greek public market. The Greek government banned free plastic bags at the start of 2018. (Photo: Giannis Papanikos/Shutterstock)

The European Union is following a similar path for its 28 member states in an effort to curb the use of plastics that "take five seconds to produce, you use it for five minutes and it takes 500 years to break down again," Frans Timmermans, the first vice president of the European Commission, the body responsible for managing the EU's day-to-operations, told the Guardian in January 2018.

Plenty of countries within the EU have their own plans in place to reduce plastic consumption, but the EU aims to have all packaging on the continent be reusable or recyclable by 2030. But first, they have to decide the best course of action to achieve that end.

The first step is an "impact assessment" to determine the best way to tax the use of single-use plastics. The EU also wants its member states to reduce the use of bags per person from 90 a year to 40 by 2026, to promote easy access to tap water on the streets to reduce the demand for bottled water and to improve states' ability to "monitor and reduce their maritime litter."

In October 2018, the EU voted overwhelmingly to ban a wide range of single-use plastics in every member state. The European Parliament voted 571-53 to forbid the use of plastics such as plates, cutlery, straws, cotton buds and even "products made of oxo-degradable plastics, such as bags or packaging and fast-food containers made of expanded polystyrene."

For other disposable items that don't have an alternative replacement, the EU ruled that member states have to reduce consumption by at least 25 percent by 2025. "This includes single-use burger boxes, sandwich boxes or food containers for fruits, vegetables, desserts or ice creams. Member states will draft national plans to encourage the use of products suitable for multiple use, as well as re-using and recycling.

Other plastic items like beverage bottles will have to be recycled by 90 percent by 2025 as well. Another goal is to reduce cigarette filters that contain plastic by 50 percent by 2025 and 80 percent by 2030. The EU also wants member states to ensure that ghost nets and other fishing gear are recycled by at least 15 percent by 2025.

All these regulations may seem overly ambitious in such a short time period, but Belgian European Parliament member Frédérique Ries, who is responsible for this bill, is optimistic these goals can be accomplished.

"We have adopted the most ambitious legislation against single-use plastics. It is up to us now to stay the course in the upcoming negotiations with the Council, due to start as early as November. Today’s vote paves the way to a forthcoming and ambitious directive," wrote Ries. "It is essential in order to protect the marine environment and reduce the costs of environmental damage attributed to plastic pollution in Europe, estimated at 22 billion euros by 2030."

The United Kingdom, which is still in the process of Brexiting from the EU, likely won't be subject to these regulations. However, as MNN's Matt Hickman reports, there's a sizable effort underway to reduce it use of plastic.

Other nations following suit

In August 2018, New Zealand's Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced the country would phase out plastic bags within a year.

"We’re phasing out single-use plastic bags so we can better look after our environment and safeguard New Zealand’s clean, green reputation," Ardern told The Guardian. "Every year in New Zealand we use hundreds of millions of single-use plastic bags. A mountain of bags, many of which end up polluting our precious coastal and marine environments and cause serious harm to all kinds of marine life, and all of this when there are viable alternatives for consumers and business."

Businesses will have six months to stop distributing plastic bags or face fines up to NZ $100,000. Many supermarket chains and major retailers have already committed to stop using plastic bags by the end of the year.

Ardern said many Kiwis welcome the ban and cited a petition signed by more than 65,000 citizens calling for it. However, the same reaction can't be said for its neighboring country, Australia.

Most territories and states in Australia have banned single-use, lightweight plastic bags except for New South Wales and Victoria — home to the country's largest cities, Sydney and Melbourne.

A sign, seen in a Coles supermarket, advises its customers of its plastic bag free in Sydney on July 2, 2018. (Photo: PETER PARKS/AFP/Getty Images)

A sign, seen in a Coles supermarket, advises its customers of its plastic bag free in Sydney on July 2, 2018. (Photo: PETER PARKS/AFP/Getty Images)

However, there was an uproar after Woolworth's and Coles, two large retail chains, tried to implement a ban on plastic bags. Many customers protested and after just several weeks Coles decided to sell reusable plastic bags for a small fee in lieu of the lightweight bags. "Some customers told us they needed more time to make the transition to re-usable bags," a Coles spokesperson told CNN.

Local Australian news outlets reported that some customers accused Coles of a marketing ploy by charging for reusable bags. The Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association also reported in July that a Woolsworth employee was attacked by a customer who was upset over the ban. The organization surveyed 120 employees and found that 50 reported being harassed by customers.

Australia isn't the only the continent to experience various reactions to plastic bags. Africa has its own mix of success.

African countries have seen mixed success

Plenty of African nations have engaged in curbing the use of plastic bags over the years. Some countries, including Gambia, Senegal and Morocco, have banned plastic bags, while others, like Botswana and South Africa, have instituted levies on plastic bags.

The success of these efforts vary from country to country; in fact, there's a black market for plastic bags in a few of them. The levy on thicker plastic bags in South Africa, for instance, has been a partial failure, according to a University of Cape Town 2010 study [PDF], due to the levy simply not being high enough, so consumers incorporate the cost into their purchases. Meanwhile, Rwanda saw an uptick in black market sales and smuggling of plastic bags following a 2008 ban. Police have set up checkpoints at various border crossings to search people for the contraband.

In perhaps the continent's longest-running plastic bag struggle, Kenya instituted the world's toughest ban on plastic bags in August 2017, with punishment ranging from steep fines to prison sentences. This represented the country's most severe attempt to ban the use of plastic bags over a 10-year effort. Even this, however, hasn't stopped the production of plastic bags, and night raids have been considered to disrupt the illegal manufacturing of plastic bags.

Banning plastics is tricky to navigate in the U.S.

A few U.S. cities are making efforts to reduce the use of plastic utensils and straws. (Photo: Kent Sievers/Shutterstock)

A few U.S. cities are making efforts to reduce the use of plastic utensils and straws. (Photo: Kent Sievers/Shutterstock)

This might not surprise you, but plastic bag politics in the U.S. are decidedly scattershot. Cities and their respective counties may end up with different policies in place, with cities acting ahead of their counties, which can cause confusion if you need to go shopping in one city on your way home to another city but you don't have any reusable bags with you. While a city may pass an ordinance banning plastic bags, the state could effectively overturn that ruling, which is what happened in Texas.

The city of Laredo banned plastic bags several years ago, but the Laredo Merchants Association challenged that decision in 2015 saying the state's law, the Texas Solid Waste Disposal Act, protected a business' right to use plastic bags. The city argued that the statute fell under an anti-littering ordinance, and the case was taken up by the Texas Supreme Court this year. The court voted unanimously that the city law was invalid because the state's law usurps the city. The court's ruling could ultimately affect other Texas cities that have also sought to ban plastic bags.

However other states, like Florida and Arizona, have banned the ban of plastic bags, while South Carolina is close to doing the same. While that eliminates confusion for sure, it doesn't actually solve the environmental problem.

Even when a state ban is in effect, that may not be the end-all, be-all answer. California as a state banned the use of plastic bags in grocery stories, retail stores with a pharmacy, food marts and liquor stores in 2016, but local municipalities that had bans in effect prior to Jan. 1, 2015, have beeen allowed to operate under their laws, essentially superseding the state ban. The differences largely come down to the price for a paper bag, however. (The state ban requires a 10-cent charge for a paper bag.)

One company is even jumping on the bandwagon. Kroger announced in August 2018 that it would stop using plastic bags by 2025.

Banning other plastic items, like straws and utensils, is gaining some steam, but only at the local level. For instance, Seattle's ban on plastic straws and utensils goes into effect on July 1 in all places that serve food and drinks (plastic bags have been banned in the city since 2011). Some establishments around the city cut out straws in September 2017, when the ban was announced, while other venues, like CenturyLink Field, SafeCo Field, made the switch to compostable straws and utensils before the city's ban. Indeed, SafeCo recycles or composts 96 percent of its waste.

Restaurants in other cities, including San Diego; Huntington Beach, California; Asbury Park, New Jersey; New York City; Miami; Bradenton, Florida, have pledged to either ban straws entirely, or simply not provide them unless a customer asks for them, according to a June 2017 article in the Washington Post.

As you can see, it's a patchwork approach to a global problem.

Editor's note: This article has been updated since it was originally published in March 2018.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)