Photographs by Evan Kafka

Update (3/3/14): After this story went to press, the US Food and Drug Administration published a paper

finding that BPA was safe in low doses. However, the underlying testing

was done on a strain of lab rat known as the Charles River Sprague

Dawley, which doesn't readily respond to synthetic estrogens, such as

BPA. And, due to laboratory contamination, all of the animals—including

the control group—were exposed to this chemical. Academic scientists say

this raises serious questions about the study's credibility. Stay tuned

for more in-depth reporting on the shortcomings of the FDA's most

recent study.

Each night at dinnertime, a

familiar ritual played out in Michael Green's home: He'd slide a

stainless steel sippy cup across the table to his two-year-old daughter,

Juliette, and she'd howl for the pink plastic one. Often, Green gave

in. But he had a nagging feeling. As an environmental-health advocate,

he had fought to rid sippy cups and baby bottles of the common plastic

additive bisphenol A (BPA), which mimics the hormone estrogen and has

been linked to a long list of serious health problems. Juliette's sippy

cup was made from a new generation of BPA-free plastics, but Green, who

runs the Oakland, California-based Center for Environmental Health, had

come across research suggesting some of these contained synthetic

estrogens, too.

He pondered these findings as the center prepared for its anniversary

celebration in October 2011. That evening, Green, a slight man with

scruffy blond hair and pale-blue eyes, took the stage and set Juliette's

sippy cups on the podium.

He recounted their nightly standoffs.

"When she wins…every time I worry about what are the health impacts of

the chemicals leaching out of that sippy cup," he said, before listing

some of the problems linked to those chemicals—cancer, diabetes,

obesity. To help solve the riddle, he said, his organization planned to

test BPA-free sippy cups for estrogenlike chemicals.

The center shipped Juliette's plastic cup, along with 17 others purchased from Target, Walmart, and Babies R Us, to

CertiChem,

a lab in Austin, Texas. More than a quarter—including Juliette's—came

back positive for estrogenic activity. These results mirrored the lab's

findings in its broader National Institutes of Health-funded research on

BPA-free plastics. CertiChem and its founder,

George Bittner, who is also a professor of neurobiology at the University of Texas-Austin, had

recently coauthored a paper in the NIH journal

Environmental Health Perspectives.

It

reported

that "almost all" commercially available plastics that were tested

leached synthetic estrogens—even when they weren't exposed to conditions

known to unlock potentially harmful chemicals, such as the heat of a

microwave, the steam of a dishwasher, or the sun's ultraviolet rays.

According to Bittner's research, some BPA-free products actually

released synthetic estrogens that were

more potent than BPA.

Estrogen

plays a key role in everything from bone growth to ovulation to heart

function. Too much or too little, particularly in utero or during early

childhood, can alter brain and organ development, leading to disease

later in life. Elevated estrogen levels generally increase a woman's

risk of breast cancer.

Estrogenic chemicals found in many common products have been linked

to a litany of problems in humans and animals. According to one study,

the pesticide atrazine can turn male frogs female. DES, which was once

prescribed to prevent miscarriages, caused obesity, rare vaginal tumors,

infertility, and testicular growths among those exposed in utero.

Scientists have tied BPA to ailments including asthma, cancer,

infertility, low sperm count, genital deformity, heart disease, liver

problems, and ADHD. "Pick a disease, literally pick a disease," says

Frederick vom Saal, a biology professor at the University of Missouri-Columbia who studies BPA.

BPA exploded into the headlines in 2008, when stories about "toxic baby bottles" and "poison" packaging became ubiquitous.

Good Morning America issued a "consumer alert."

The New York Times urged Congress to ban BPA in baby products. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.)

warned in the Huffington Post

that "millions of infants are exposed to dangerous chemicals hiding in

plain view." Concerned parents purged their pantries of plastic

containers, and retailers such as Walmart and Babies R Us started

pulling bottles and sippy cups from shelves. Bills banning BPA in infant

care items began to crop up in states around the country.

Today many plastic products, from sippy cups and blenders to

Tupperware containers, are marketed as BPA-free. But Bittner's

findings—some of which have been confirmed by other scientists—suggest

that many of these alternatives share the qualities that make BPA so

potentially harmful.

Those startling results set off a bitter fight with the

$375-billion-a-year plastics industry.

The American Chemistry Council,

which lobbies for plastics makers and has sought to refute the science

linking BPA to health problems, has teamed up with

Tennessee-based Eastman Chemical—the

maker of Tritan, a widely used plastic marketed as being free of

estrogenic activity—in a campaign to discredit Bittner and his research.

The company has gone so far as to tell corporate customers that the

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rejected Bittner's testing

methods. (It hasn't.) Eastman also sued CertiChem and its sister

company, PlastiPure, to prevent them from publicizing their findings

that Tritan is estrogenic, convincing a jury that its product displayed

no estrogenic activity. And it launched a PR blitz touting Tritan's

safety, targeting the group most vulnerable to synthetic estrogens:

families with young children.

"It can be difficult for

consumers to tell what is really safe," the vice president of Eastman's

specialty plastics division, Lucian Boldea,

said in one web video,

before an image of a pregnant woman flickered across the screen. With

Tritan, he added, "consumers can feel confident that the material used

in their products is free of estrogenic activity."

"A poison kills you," says biology

professor Frederick vom Saal. "A chemical like BPA reprograms your cells

and ends up causing a disease in your grandchild that kills him."

Eastman's offensive is just the latest in a wide-ranging industry

campaign to cast doubt on the potential dangers of plastics in food

containers, packaging, and toys—a campaign that closely resembles the

methods Big Tobacco used to stifle scientific evidence about the dangers

of smoking. Indeed, in many cases, the plastics and chemical industries

have relied on the same scientists and consultants who defended Big

Tobacco.

These efforts, detailed in internal industry documents revealed

during Bittner's legal battle with Eastman, have sown public confusion

and stymied US regulation, even as BPA bans have sprung up elsewhere in

the world. They have also squelched debate about the safety of plastics

more generally. All the while, evidence is mounting that the products so

prevalent in our daily lives may be leaching toxic chemicals into our

bodies, with consequences affecting not just us, but many generations to

come.

The fight over the safety of plastics traces back to 1987, when Theo Colborn, a

60-year-old grandmother with a recent Ph.D. in zoology,

was hired to investigate mysterious health problems in wildlife around

the Great Lakes.

Working for the Washington, DC-based Conservation

Foundation (now part of the World Wildlife Fund), she began collecting

research papers. Before long, her tiny office was stacked floor to

ceiling with cardboard boxes of studies detailing a bewildering array of

maladies—cancer, shrunken sexual organs, plummeting fertility, immune

suppression, birds born with crossed beaks and missing eyes. Some

species also suffered from a bizarre syndrome that caused seemingly

healthy chicks to waste away and die.

While the afflictions and species varied widely, Colborn eventually

realized they had two factors in common: The young were hardest hit,

and, in one way or another, all of the animals' symptoms were linked to

the endocrine system, the network of glands that controls growth,

metabolism, and brain function, with hormones as its chemical

messengers. The system also plays a key role in fetal development.

Colborn suspected that synthetic hormones in pesticides, plastics, and

other products acted as "hand-me-down poisons," with parents' exposure

causing affliction in their offspring.

Initially, her colleagues were

skeptical. But Colborn collected data and tissue samples from far-flung

wildlife populations and unearthed previously overlooked studies that

supported her theory. By 1996, when Colborn copublished her landmark

book

Our Stolen Future, she

had won over many skeptics. Based partly on her research, Congress

passed a law that year requiring the EPA to screen some 80,000

chemicals—most of which had never undergone any type of safety

testing—for endocrine-disrupting effects and report back by 2000.

Around this time, the University of Missouri's vom Saal, a garrulous

biologist who previously worked as a bush pilot in Kenya, began studying

the effects of synthetic estrogens on fetal mouse development.

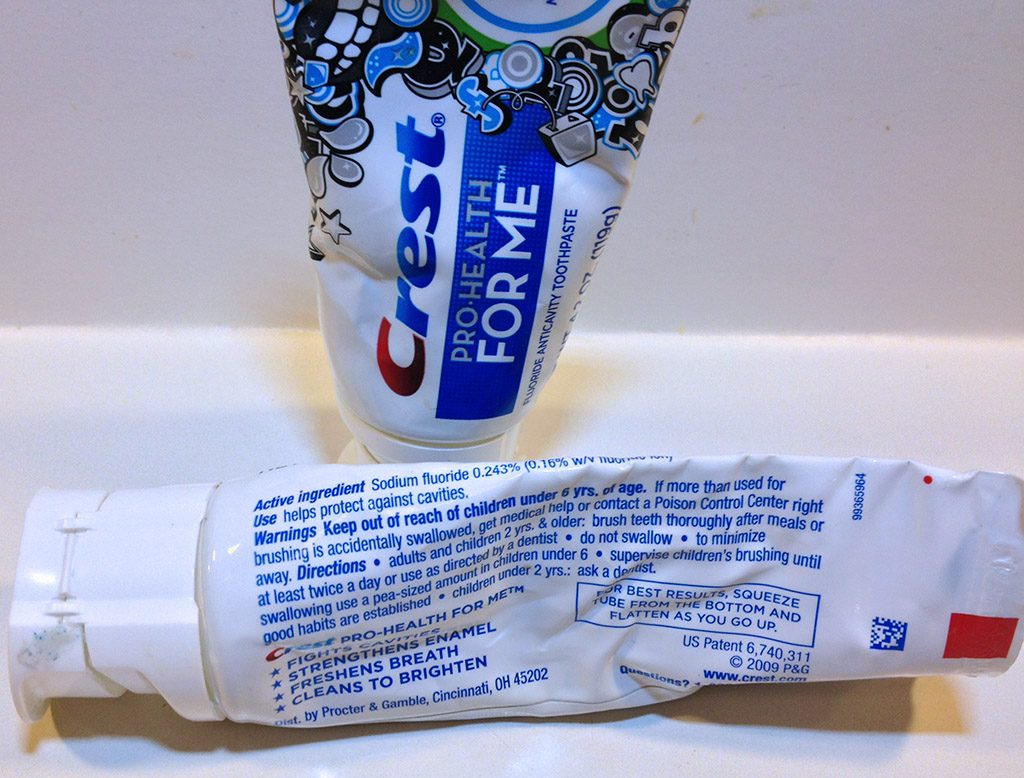

The

first substance he tested was BPA, a chemical used in clear, hard

plastics, particularly the variety known as polycarbonate, to make them

more flexible and durable. (It's also found in everyday items, from

dental sealants and hospital blood bags to cash register receipts and

the lining of tin cans.) Naturally occurring estrogens bind with

proteins in the blood, limiting the amount that reaches estrogen

receptors. But vom Saal found this wasn't true of BPA, which bypassed

the body's natural barrier system and burrowed deep into the cells of

laboratory mice.

Vom Saal suspected this would make BPA "a hell of a lot more potent" in small doses. Working with colleagues Susan Nagel and

Wade Welshons,

a professor of veterinary biology, he began testing the effects of BPA

at amounts 25 times lower than the EPA's safety threshold.

In the late

1990s, they published two studies finding that male mice whose mothers

were exposed to these low doses during pregnancy had enlarged prostates

and low sperm counts. Even in microscopic quantities, it seemed, BPA

could cause the kinds of dire health problems Colborn had found in

wildlife. Before long, other scientists began turning up ailments among

animals exposed to minute doses of BPA.

These findings posed a direct threat to plastics and chemical makers,

which fought back using tactics the tobacco makers had refined to an

art form. By the late 1990s, when tobacco companies agreed to drop

deceptive marketing practices under a settlement agreement with 46

states, many of the scientists and consultants on the industry's payroll

transitioned seamlessly into defending BPA.

Plastics and chemical interests worked closely with the Weinberg Group, which had run

Big Tobacco's White Coat Project—an

effort to recruit scientists to create doubt about the health effects

of secondhand smoke.

Soon Weinberg, which bills itself as a "product

defense" firm, was churning out white papers and lobbying regulators. It

also underwrote a trade group with its own scientific journal,

Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, which published studies finding BPA was safe.

The industry also worked hand in glove with the Harvard Center for

Risk Analysis, a think tank affiliated with the university's school of

public health that has a history of accepting donations from

corporations and then publishing research favorable to their products.

In the early 1990s, its founder, John D. Graham—who was later tapped as

George W. Bush's regulatory czar—

lobbied to quash an EPA finding that secondhand smoke caused lung cancer, while soliciting large contributions from Philip Morris.

In 2001, as studies on BPA stacked up, the American Chemistry Council

enlisted the center to convene a panel of scientists to investigate

low-dose BPA. The center paid panelists $12,000 to attend three

meetings,

according to Fast Company.

Their final report, released in 2004, drew on just a few

industry-favored studies and concluded that the evidence that low-dose

BPA exposure harmed human health was "very weak."

By this point, roughly

100 studies on low-dose BPA were in circulation. Not a single

industry-funded study

found it harmful,

but 90 percent of those by government-funded scientists discovered

dramatic effects, ranging from an increased breast cancer risk to

hyperactivity. Four of the 12 panelists later insisted the center scrub

their names from the report because of questions about its accuracy.

Chemical interests, meanwhile, forged deep inroads with the Bush

administration, allowing them to covertly steer the regulatory process.

For decades, the Food and Drug Administration has assured lawmakers and

the public that BPA is safe in low doses. But

a 2008 investigation by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

revealed that the agency had relied on industry lobbyists to track and

evaluate BPA research, and had based its safety assessment largely on

two industry-funded studies—one of which had never been published or

peer reviewed.

The panel the EPA appointed to develop guidelines for its

congressionally mandated endocrine disruptor screening was also stocked

with industry-backed scientists. It included Chris Borgert, a toxicology

consultant who had worked closely with Philip Morris to discredit EPA

research on secondhand smoke. He later served as the president of the

International Society of Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, the

Weinberg Group-sponsored outfit, which met in the offices of a plastics

lobbyist.

Members of the EPA panel say Borgert seemed determined to sandbag the

process. "He was always delaying, always trying to confuse the issue,"

recalls one participant. And the screening approach the EPA settled on

came straight from the industry's playbook. Among other things, the

chemicals would be tested on a type of rat known as the Charles River

Sprague Dawley—which, oddly, doesn't respond to synthetic hormones like

BPA.

"Like the tobacco companies, they want to

set up a standard of proof that is unreachable," says Stanton Glantz.

"If they set the standard of proof, they've won the fight."

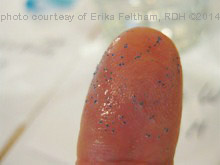

How best to test for estrogenic activity would become a key front in

the fight over plastic safety. The American Chemistry Council joined

forces with an unlikely ally, PETA, to fight large-scale chemical-safety

testing on animals.

At the same time, Borgert and other industry-funded

scientists made the case that the other common method for testing—using

cells that respond in the presence of estrogen—did not necessarily tell

us how a substance would affect animals or humans. In fact, a massive,

ongoing NIH-run study has found that cell-based tests track closely with

animal studies, which have accurately predicted the effects of

synthetic estrogens, particularly DES and BPA, on humans.

Stanton Glantz, who directs the Center for Tobacco Control Research

and Education at the University of California-San Francisco, argues the

chemical industry's real aim in challenging specific testing methods is

to undermine safety testing altogether. "Like the tobacco companies,

they want to set up a standard of proof that is unreachable," he says.

"If they set the standard of proof, they've won the fight."

During the height of the battle

over BPA, vom Saal periodically traveled to Texas and huddled around the

dining table with his old friend George Bittner, whose home overlooks a

walnut grove on the outskirts of Austin. Bittner, who holds a Ph.D. in

neuroscience from Stanford, is quirky and irascible.

But he has a

brilliant mind for science and an interest in applying it to real-world

problems—in his lab at UT-Austin, he had developed a nerve-regeneration

technique that had helped crippled rats walk within days. And he had

taken a keen interest in vom Saal's research on endocrine disruption.

"It struck me as the most important public health issue of our time,"

Bittner told me when we met at his lab. "These chemicals have been

correlated with so many adverse effects in animal studies, and they're

so pervasive. The potential implications for human health boggle the

mind."

In the late 1990s, Bittner—a squat, ruddy man with thinning red hair

and Napoleon Dynamite glasses who had made a tidy sum investing in real

estate and commodities—began mulling the idea of launching a private

company that worked with manufacturers and public health organizations

to test products for endocrine disruptors. He believed this approach

could help raise awareness and break the regulatory logjam—while also

reaping a profit.

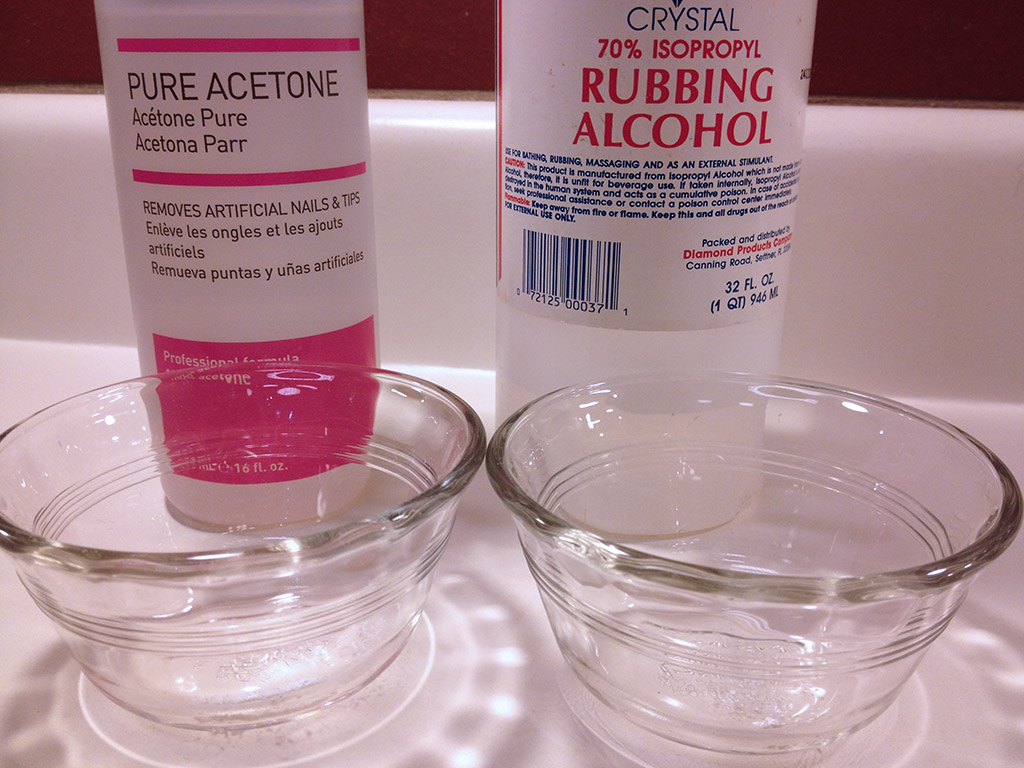

In 2002, armed with a $91,000 grant from the National Institutes of

Health, Bittner launched a pair of companies: CertiChem, to test

plastics and other products for synthetic estrogens, and PlastiPure, to

find or develop nonestrogenic alternatives. Bittner then enlisted

Welshons to design a special test using a line of breast cancer cells,

which multiply rapidly in the presence of estrogen. It features a

robotic arm, which is far more precise than a human hand in handling

microscopic material.

But before long Bittner began butting heads with Welshons and vom

Saal. Bittner wanted the researchers to sign over the rights to the test

Welshons had developed, while they insisted it belonged to the

University of Missouri. Eventually, they had a bitter falling out.

Welshons and vom Saal filed a complaint with the NIH, alleging that

Bittner had misrepresented data from Welshons' lab in a brochure.

(Bittner maintains that he merely excluded data from contaminated

samples; the institute found no evidence of wrongdoing.)

Bittner,

meanwhile, enlisted

V. Craig Jordan,

a pharmacology professor at Georgetown University with an expertise in

hormones—he discovered a now-common hormone therapy that blocks the

spread of breast cancer—to refine the testing protocol. By 2005, Bittner

had opened a commercial lab in a leafy office park in Austin. He

managed to attract some big-name clients, including Whole Foods, which

hired CertiChem to advise it on endocrine-disrupting chemicals and test

some of its products.

At this point, BPA was among the most studied chemicals on the

planet. In November 2006, vom Saal and a top official at the National

Institute of Environmental Health Sciences convened a group of 38

leading researchers from various disciplines to evaluate the 700-plus

existing studies on the subject.

The group later issued a "

consensus statement"

that laid out some chilling conclusions: More than 95 percent of people

in developed countries were exposed to levels of BPA that are "within

the range" associated with health problems in animals, from cancer and

insulin-resistant diabetes to early puberty. The scientists also found

that there was "great cause for concern with regard to the potential for

similar adverse effects in humans," especially given the steep uptick

in these same disorders.

At the same time, a new body of research was finding that BPA altered

animals' genes in ways that caused disease. For instance, it could

switch off a gene that suppresses tumor growth, allowing cancer to

spread. These genetic changes were passed down across generations. "A

poison kills you," vom Saal explains. "A chemical like BPA reprograms

your cells and ends up causing a disease in your grandchild that kills

him."