published April 19th in

the Atlantic by

Veronique Greenwood

An interview with the author of Plastic: A Toxic Love Story on the origins and uses of plastic—and how it abuses us

In 1941, imagining the world that plastic would make possible, a pair of British chemists wrote of "a world of color and right shining surfaces...a world in which man, like a magician, makes what he wants for almost every need." Plastic has indeed completely transformed our lives—everything from modern medicine to food safety has been made possible by its fantastic and varied properties.

But we've gradually realized that plastic has a dark side. It leaches chemicals that have been found in our bloodstreams and may cause permanent damage to us and our children, at the same time that it accrues in the oceans with no sign of breaking down.

In

Plastic: A Toxic Love Story (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, April 18, $27), writer Susan Freinkel explores the tales of eight plastic objects—the comb, the chair, the Frisbee, the IV bag, the Bic lighter, the grocery bag, the soda bottle, and the credit card—to explore how plastic's fate became so entwined with our own. By turns whimsical and profoundly disturbing,

Plastic gives a lucid, comprehensive, and, ultimately, galvanizing account of our past with plastic and what our future may be.

I asked Freinkel about plastic's origins, its dangers, and what we can do to turn this love affair around.

When the first plastic, celluloid, was developed, it was a solution to a pressing environmental problem: the hunting of elephants to extinction for ivory. What led up to celluloid's development, and what was the contemporary response to plastic?

When the first plastic, celluloid, was developed, it was a solution to a pressing environmental problem: the hunting of elephants to extinction for ivory. What led up to celluloid's development, and what was the contemporary response to plastic?

For most of human history people fashioned the things they wanted and needed from materials of the natural world. But by the mid-19th century, they were starting to recognize the limits of nature's bounty and the physical limitations of natural materials. Those fears about an impending ivory shortage led a New York billiards supplier in 1863 to run an ad offering $10,000 in gold to anyone who could come up with a suitable alternative.

Eventually, this led to the invention of celluloid, which is considered a semi-synthetic because it starts with cellulose derived from plants. People loved it; it was now possible to mass-produce all kinds of consumer goods far more cheaply. An ivory comb would have been beyond the reach of the average shop girl, but she could certainly afford a beautiful faux-ivory one made of celluloid. Indeed, people continued to be enthralled with plastics for decades. Plastics promised abundance on the cheap.

However, our enthusiasm for plastic and the paucity of laws regulating the materials we package food and drink in, wear, sit on, sleep on, and use nearly every second of every day has meant that it's taken us a while to realize that plastic has a dark side, both in terms of the chemicals it leaches and its persistence in the environment. What have been the landmark discoveries that have caused us to start trying to reform this relationship?

Health concerns about plastic arise from a series of discoveries that have made clear plastics are not the inert, stable substances we once thought. It began in the 1970s with a pair of revelations: one, that vinyl readily leached phthalates, chemicals used to make the plastic soft and flexible, and two, that many people had traces of phthalate in their bloodstreams, thanks to casual contact with various everyday plastic things from cars to toys to wallpaper. Writing about one of the reports, a

Washington Post reporter observed, "human are just a little plastic now." What that meant was not totally clear: At the time, experts concluded that it didn't mean much because the amounts that leached out and got into people's bodies were so minute.

Japanese scientist Hideshige Takada added another reason to worry when he reported that these tiny bits of plastic sop up persistent pollutants such as PCBs that are already present in the ocean.

But new findings since the 1990s have made researchers rethink the risks. Animal studies showed that some chemicals in plastics, notably phthalates and Bisphenol A, can mimic and disrupt hormones, with profound long-term effects if the animal was exposed during critical periods of development—in utero, in infancy, or even different points during childhood. Then being even a little bit plastic could potentially have a big effect.

Around the same time the Centers for Disease Control developed new, far more sensitive methods of measuring people's exposure to chemicals, and began producing biomonitoring studies showing that most Americans showed traces of phthalates, Bisphenol A, and other chemicals commonly used in plastics in their blood, urine, and other bodily fluids.

Finally a variety of epidemiological studies have found associations between exposures to these chemicals and various health conditions, such as diabetes, obesity, infertility, asthma, and even Attention Deficit Disorder. All the dots haven't been connected by any means, but their presence on the public health map has ratcheted up concerns.

Awareness of plastic pollution is also fairly recent. Although there have been scattered reports about plastic trash in the ocean going back to the 1960s, two recent developments sparked a new sense of urgency. In 1997, a sailor named Charles Moore took his boat through a rarely traveled area of the Pacific Ocean where converging ocean currents cause debris from Asia and North America to accumulate. Moore was shocked to see a steady stream of plastic debris float by day after day, which became known as the "garbage patch." And if anything testifies to the long and devastating reach of our throwaway culture, it's the presence of things like disposable lighters or toothbrushes or water bottles in the remote stretches of the ocean.

Another landmark was a 2004 study by English scientist Richard Thompson showing an exponential increase over the past several decades in the amount of tiny plastic fibers and fragments in the North Sea. This "microdebris" is what's left after waves and the sun have broken up bigger pieces of plastic trash. Until then people's idea of plastic pollution in the ocean was focused on the big stuff, like six-pack rings or drift nets and the ways those could threaten wildlife. Thompson's work drew attention to these tiny plastic bits, which, it turns out, are suffused throughout all the world's oceans and can never be cleaned up. Meanwhile, Japanese scientist Hideshige Takada added another reason to worry when he reported that these tiny bits sop up persistent pollutants such as PCBs that are already present in the ocean. If fish and other marine animals eat these plastic fragments, as it appears they do, is there risk these toxic chemicals could work their way up the food chain, back to us?

The people who know intimately about the dangers of plastic—the nurses in the neonatal ward, the researchers who study leaching—what do they do to protect themselves from it?

The people who know intimately about the dangers of plastic—the nurses in the neonatal ward, the researchers who study leaching—what do they do to protect themselves from it?

The one measure everyone recommends is not to cook or microwave food in plastic since that can accelerate the leaching process. Some are cautious about storing leftovers in plastic containers and some only use metal water bottles—or at least take that precaution with their children. Most are careful about not eating too many canned foods, since the lining of cans often contains Bisphenol A. (Indeed, a recent study showed eating fresh fruits and vegetables for just three days could lower people's BPA levels.) Those with kids look for toys and products that are free of phthalates or BPA.

But given the current framework of laws and policies regulating chemicals in the U.S. and the utter ubiquity of plastics, there's only so much an individual can do. U.S. law tends to treat chemicals as safe until proven otherwise. As a result, most of the tens of thousands of chemicals in commerce have been poorly tested to determine their effects on the environment or human health.

In Europe, by contrast, the burden of proof is on safety rather than danger. European regulators act on the precautionary principle, the idea of preventing harm before it happens, even in the face of scientific uncertainty. A new E.U. law enacted in 2007 requires testing of newly introduced chemicals, as well as those already in heavy use, with the burden on manufacturers to demonstrate they can be used safely. To comply with that law, American manufacturers are already selling products in European markets that have been reformulated to comply with the precautionary principle. For instance, a phthalate alternative, DINCH, is being used in vinyl medial supplies sold in Europe. But not here.

When you say our love affair with plastic needs couples therapy, you've nailed the difficulty of the transition we need to make. What kind of change is possible, in terms of regulation? And what kind of reasoned, thoughtful action can an individual take that will actually make a difference?

Making over our relationship with plastic requires change at all levels—from government, industry, and individuals. I don't discount the value of what individuals can do. If we all made more of an effort to reduce our reliance on throwaway plastics (e.g., carry your own bag and bottle), to reuse more of the plastics that come through our lives, and to recycle as much as possible, that would help put a dent in plastic waste and pollution. We also can use our power as consumers to help shape the choices we are offered, making more conscious choices at the store and rejecting over-packaged goods and products that can't be reused or recycled. The power of the purse is why Walmart, Target, and other big box stores stopped selling baby bottles that contained Bisphenol A, even though the chemical has not been outlawed. We can also join forces in political campaigns to press for change. Pressure by the grassroots group Healthcare Without Harm helped persuade many of the country biggest hospital chains and hospital supply purchasers to stop using medical devices made of vinyl.

But individual actions alone are unlikely to bring about the scale of change that we need. The European experience suggests that laws that hold industry accountable for the products it puts into the marketplace can have a powerful effect. The E.U.'s tougher chemical laws have galvanized greater use of "green" chemicals. I'm also impressed by the effect of Europe's extended producer responsibility laws—measures that make companies responsible for what happens to their products and packaging at the end of their useful lives. When companies, rather than taxpayers, have to pay for collecting and disposing of plastic waste, dramatic changes happen: They use less packaging, they use materials that are easily recycled, and overall recycling rates go up.

These are the kinds of policies that could take us to a new level in our relationship with plastics, so we can reap the benefits plastics have to offer without the dangers.

Images (top to bottom): ingridtaylar/flickr, Library of Congress, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

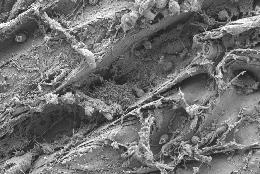

Electron microscopy reveals the inhabitants of a plastic bag fished from the Sargasso Sea.T. Mincer/G. Proskurowski

Electron microscopy reveals the inhabitants of a plastic bag fished from the Sargasso Sea.T. Mincer/G. Proskurowski